As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Introduction

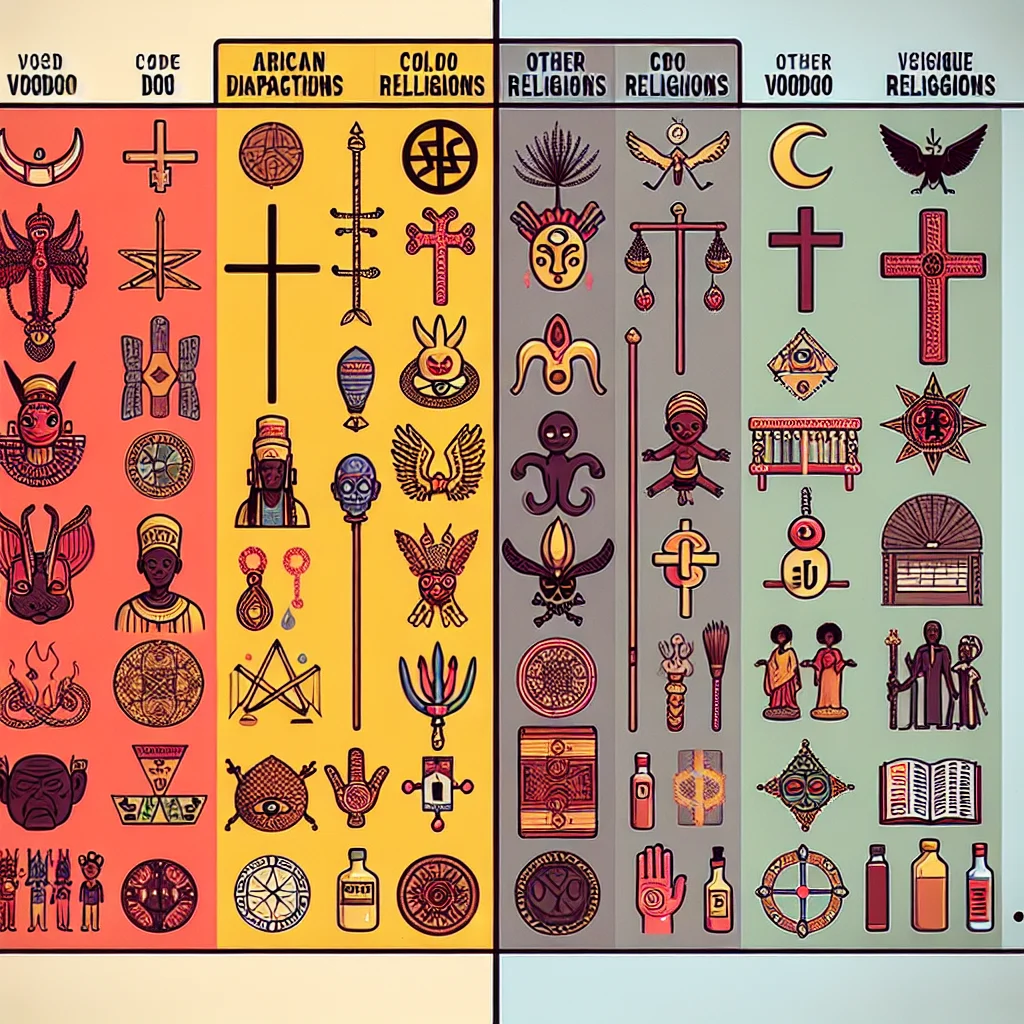

Voodoo, a religion that rose from the blending of African cultural and spiritual practices with elements of Christianity, is just one of many African Diaspora religions. The term “African Diaspora religions” encompasses practices such as Santería, Candomblé, and Rastafarianism, that have also emerged from the fusion of African traditions with other cultural elements across the globe. In the contemporary world, these religions are practiced by millions, each with its unique rituals, deities, and symbolic meanings. According to Pew Research, more than 7% of people in the Caribbean practice some form of African Diaspora religion, indicating their lasting significance and diverse presence today. By examining the distinctive characteristics that set Voodoo apart from other African Diaspora religions, we can better understand and appreciate the rich tapestry of spiritual practices originating from Africa.

Origins and Historical Context

Voodoo originated primarily in Haiti, rooted in the traditions of West African Vodun and influenced by French Catholicism during the colonial period. On the other hand, Santería, also known as Lukumi, developed in Cuba through the merging of Yoruba religious practices with elements of Spanish Catholicism. Candomblé, which emerged in Brazil, combines Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu beliefs with Portuguese Catholic influences. These historical contexts have shaped the respective practices and belief systems of each religion in unique ways.

Deities and Spiritual Entities

Voodoo’s pantheon consists of spirits known as Loa, each of whom serves distinct roles and symbolizes various aspects of life. In Santería, the deities are referred to as Orishas, inherited from the Yoruba tradition, each overseeing specific natural and social phenomena. Candomblé also worships Orishas along with Voduns and Inquices, but with distinctive names and attributes adapted to the Brazilian context. Unlike these religions, Rastafarianism does not focus on a pantheon of deities but venerates figures such as Emperor Haile Selassie, viewing him as a divine entity.

Rituals and Ceremonies

Voodoo ceremonies often involve drumming, dancing, and spirit possession, where participants become mediums for the Loa. These rituals are deeply communal and feature altars adorned with symbolic offerings. In contrast, Santería rituals incorporate animal sacrifices, drumming, and trance, specifically designed to honor and invoke the Orishas. Candomblé practices include elaborate dances, music, and offerings presented to deities, each corresponding to particular natural elements like water, earth, and sky. Rastafarian rituals, or “Nyabinghi” gatherings, focus on chanting, drumming, and the smoking of sacramental cannabis as means to commune with the divine.

Syncretism with Christianity

Voodoo is known for its syncretism with Roman Catholicism, where Catholic saints are integrated into the pantheon of Loa and observances align with the Christian liturgical calendar. Santería similarly integrates Catholic saints, often equating them with Orishas to preserve the tradition under oppressive colonial regimes. Candomblé maintains a more distinct separation between its African deities and Catholic saints, despite the historical blending of cultures. Rastafarianism, however, diverges significantly by interpreting the Bible through an Afro-centric lens rather than blending its practices with traditional Christianity.

Sacred Spaces and Altars

The Voodoo temple, known as the “hounfour,” contains altars for the Loa, often adorned with photographs, candles, and offerings. In Santería, sacred spaces are generally home altars containing images of Catholic saints, Orisha paraphernalia, and offerings. Candomblé temples, or “terreiros,” feature dedicated spaces for each Orisha, often decorated with distinct colors, symbols, and objects pertinent to the deity they honor. Rastafarian sacred spaces are less formal and range from communal gatherings to personal meditation areas, reflecting the movement’s emphasis on individual connection with the divine.

1. **Historical Origins and Geographic Roots**

When exploring *Voodoo vs other traditions* within African diaspora religions, one discovers that Voodoo, often spelled Vodou in Haiti, has its roots in the West African regions, particularly among the Fon, Ewe, and Yoruba peoples. Other African diaspora religions like Santería and Candomblé trace their origins to the Yoruba people of Nigeria and the Congo-Angolan territories. These distinct geographic origins influence various elements of belief systems, deities, and rituals.

2. **Deities and Spirit Entities**

In Voodoo, spirits known as *lwa* are venerated and serve as intermediaries between the human world and the divine. Each *lwa* has unique characteristics and roles. On the other hand, Santería followers worship *orishas*, which are spiritual entities that also serve as intermediaries but distinctly are directly linked to natural elements like rivers or mountains. Candomblé also venerates *orixás* or spirits but places a stronger emphasis on the syncretism with Catholic saints due to the influences in Brazil.

3. **Ritualistic Practices and Ceremonies**

Voodoo ceremonies typically involve intricate drumming, dancing, and spirit possession. Ritualistic practices of Santería include animal sacrifices to honor the *orishas*, divination rituals, and detailed preparation of herbs for sacred healing. Candomblé, meanwhile, emphasizes communal gatherings, music, and dance to invoke the *orixás*, using coded steps and rhythms unique to each spirit.

4. **Cosmological Beliefs and Worldview**

Voodoo cosmology is deeply rooted in the idea that spirits influence every aspect of life, and pleasing them brings balance and harmony. This belief shapes daily living and societal norms. In contrast, Santería’s cosmology incorporates a duality in the spiritual and material world, reflecting a balance between human experiences and the divine. Candomblé cosmology is akin to a richly woven tapestry where nature, spirits, and ancestors interact dynamically.

5. **Healing Practices and Herbal Medicine**

One of the central aspects of Voodoo relates to its intricate system of herbal medicine and spiritual healing, where practitioners known as *houngans* or *mambos* are skilled in creating medicinal concoctions with both spiritual and physical components. Santería uses similar healing practices but heavily relies on *ebós*, or offerings, to the *orishas* for healing. Candomblé incorporates a diverse array of African herbal traditions passed down through generations, often interwoven with Catholic rituals.

6. **Socio-Cultural Integration**

Voodoo, particularly in Haiti, is deeply integrated into socio-cultural practices and national identity. Festivals, local laws, and cultural norms often reflect Voodoo principles. In contrast, Santería in Cuba is practiced alongside Catholicism within a context that reflects syncretism, where Afro-Cuban elements are celebrated. Candomblé in Brazil often merges with mainstream cultural practices, maintaining its visibility through public festivals like Carnaval.

7. **Influence of Colonialism and Slavery**

The impact of colonization and the transatlantic slave trade has uniquely molded these religions. Voodoo has evolved amid colonial repression and syncretized elements of Christianity, creating a distinct religious framework. Santería emerged as a form of cultural and spiritual resistance among enslaved Africans in Cuba, ingeniously blending African deities with Catholic saints to preserve their religion under colonial rule. Candomblé similarly adapted and survived by merging with Catholicism and maintaining African traditions secretly.

8. **Spiritual Leadership and Hierarchical Structure**

The organizational structures of Voodoo involve *houngans* (male priests), *mambos* (female priests), and the followers, forming a hierarchical yet community-centric system. Santería’s leadership includes the *babalawos* (priests) who hold significant spiritual authority, and a focus on lineage and initiation is maintained. Candomblé’s hierarchy is complex, with various ranks such as *maes-de-santo* (female leaders) and *pais-de-santo* (male leaders), reflecting African clan systems and Catholic priesthood influences.

9. **Magical Practices and Sacred Objects**

The magical contrasts between these traditions manifest in Voodoo’s use of dolls, veves (sacred symbols), and specific ritual implements imbued with spiritual energy. Santería employs an array of religious artifacts, beads (known as *elekes*), and soperas (sacred pots for *orishas*), which are central to rituals and spiritual communication. Candomblé integrates sacred drums, elaborately decorated garments, and ritual objects that symbolize the spirit’s energy.

10. **Community and Ancestral Veneration**

Community cohesion and ancestral worship are pivotal in Voodoo, where honoring ancestors is intrinsically linked to familial and community welfare. Santería equally emphasizes the veneration of ancestors (known as *egungun*) alongside *orishas*, reflecting a dual system of spiritual acknowledgement. In Candomblé, ancestors known as *eguns* hold a profound place in communal rituals and personal spirituality.

According to a 2008 Pew Research survey, approximately 35% of Haitians identify as adherents of Voodoo, showcasing the profound impact of this religion within the country.

Core Beliefs and Deities

I remember attending a Voodoo ceremony in New Orleans where the primary focus was on spirits known as loa. These spirits acted as intermediaries between the human world and the divine, much like saints in Catholicism. Participants called upon specific loa for various needs, and the atmosphere was filled with music and dance to invoke their presence.

In contrast, while staying with friends in Brazil, I attended a Candomblé ritual. Here, the deities were called orixás, and each had a specific domain of influence like nature, health, or love. Unlike Voodoo, where the loa served as intermediaries, Candomblé’s orixás were more deeply connected to elements of nature and ancestral spirits.

When visiting a Santería community in Cuba, I found that the practice involved veneration of orichas, quite similar to the orixás in Candomblé. However, Santería combined African spiritual practices with elements of Catholicism more overtly, such as the synchronization of orichas with Catholic saints, which was less pronounced in the Voodoo practices I observed.

Ritual Practices and Ceremonies

During the Voodoo ceremony, I noticed the significant use of ritualistic drumming, singing, and dancing. Participants seemed to enter trance-like states, believed to be possessions by the loa. Offerings of food, drink, and even animal sacrifices were made to appease these spirits and ask for their blessings.

In my time with the Candomblé community, the ceremonies also featured music and dance but were more focused on individual orixás, each represented by specific colors, foods, and symbols. The ritual space, called a terreiro, was carefully maintained to foster an ideal environment for the orixás to descend and interact with worshippers.

The Santería rituals I took part in often occurred in more intimate, private settings, such as someone’s home. Here, the rituals included singing and drumming as well, but there was a stronger emphasis on divination using cowrie shells. Santeros would interpret the messages from the orichas, giving advice and guidance to participants, which was a distinctive feature not as prevalent in the Voodoo practices I witnessed.

Syncretism and Adaptation

In New Orleans Voodoo, the mingling of African traditions with Catholic elements was evident. For instance, figures like St. Peter and St. Anthony were often associated with specific loa. This syncretism made Voodoo more accessible to the existing Catholic population, allowing for smoother cultural adaptation and survival through periods of oppression.

While experiencing Candomblé in Brazil, I saw a different kind of syncretism. The orixás were often linked with Catholic saints in a similar way, but the ceremonies and altars retained a stronger traditional African essence, possibly because of Brazil’s larger Afro-Brazilian population, which enabled a closer preservation of African practices.

The syncretism in Santería, observed during my visit to Cuba, involved a direct parallel between orichas and Catholic saints. What was unique here was the added layer of Spanish cultural elements, such as the use of Spanish language prayers alongside traditional African chants. This blend created a distinctive practice that felt different from both Voodoo and Candomblé.

Geographical and Cultural Context

In New Orleans, Voodoo had evolved within the context of French Creole culture. The architecture, music, and language of the region all influenced how Voodoo practices developed. The public perception of Voodoo in New Orleans also leaned heavily on tourism, which impacted its visibility and practice.

During my time in Salvador, the heart of Afro-Brazilian culture, Candomblé was embedded into everyday life. The city’s festivals, music, and even regional cuisine were influenced by Candomblé practices. This made the religion more integrated into the daily experiences of the community, rather than something isolated or ceremonial.

In Havana, Santería seemed to permeate social and cultural norms much more subtly but no less significantly. The religion was a part of local crafts, street markets, and even national celebrations. Unlike the somewhat commercialized presentation of Voodoo in New Orleans, Santería felt more like a private spiritual practice despite its widespread influence.

1. What are the key differences between Voodoo and Santería?

Voodoo and Santería share some similarities due to their African roots but differ significantly in their rituals, deities, and cultural influences. Voodoo, primarily practiced in Haiti, is syncretized with Catholicism and incorporates a pantheon of spirits called Lwa. Santería, rooted in the Yoruba tradition, is primarily found in Cuba and integrates closely with the worship of Orishas, also aligning with Catholic saints.

2. How do the spiritual practices of Voodoo differ from those in Candomblé?

Candomblé is a Brazilian religion with origins in West Africa, particularly the Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu peoples. While both religions involve the veneration of spirits, Voodoo rituals often involve drumming, dancing, and spirit possession to invoke the Lwa. Candomblé ceremonies also feature drumming and singing but focus on the Orishas, with elaborate offerings and precise ritual practices.

3. Are the magical practices in Voodoo distinct from other African Diaspora religions?

Yes, Voodoo’s magical practices, often referred to as Hoodoo in the context of folk magic, include creating gris-gris (charm bags), using voodoo dolls, and conducting specific spells and rituals for protection, love, and healing. Other African Diaspora religions, like Santería and Candomblé, also have magical elements but they tend to focus more on divination, herbal medicine, and sacred dances to communicate with the divine.

4. What is the role of the ancestor spirits in Voodoo compared to other traditions?

In Voodoo, ancestors (often referred to as the revered dead) are venerated and believed to influence the living world. They are honored through offerings, prayers, and rituals. In other African Diaspora religions, such as Ifá and Santería, ancestor veneration also plays a crucial role, with ancestors being invoked for guidance and protection during various ceremonies and daily practices.

5. Do Voodoo practitioners use different tools and symbols than those in other African Diaspora religions?

Yes, Voodoo practitioners use specific tools like veves (sacred symbols drawn on the ground), candles, herbs, and ritual items tailored to each Lwa. Other African Diaspora religions use different sets of tools and symbols. For instance, in Santería, items like the otanes (sacred stones) and elekes (beaded necklaces) are significant, while Ifá practitioners use palm nuts and divining chains.

6. How do the initiation rites of Voodoo compare with those of other African spiritual traditions?

Voodoo initiation involves complex and confidential rites that vary depending on the specific Lwa one serves. It includes rituals to cleanse, protect, and empower the initiate. In Santería, the initiation is known as making “Ocha” and involves several stages, including divining, receiving Orishas, and a period of seclusion. Candomblé initiation also includes a seclusion period and numerous rites to connect the individual with their Orisha.

7. What is the approach to healing in Voodoo vs. other African Diaspora religions?

Healing in Voodoo frequently involves the intercession of Lwa, herbal medicine, and ritual baths. Voodoo priests (Houngans) or priestesses (Mambos) perform these ceremonies. In Santería, healing practices often involve consultations and prescriptions from Orishas through divination, along with herbal remedies and spiritual cleansings. Candomblé similarly emphasizes herbal medicine and rituals to restore spiritual balance.

8. Are there differences in the concept of the divine between Voodoo and other African spiritualities?

While Voodoo and other African Diaspora religions share a belief in a supreme deity and various lesser spirits, the pantheon and nature of these beings can differ. Voodoo’s supreme god is Bondye, who is distant and not directly involved in human affairs, leaving the Lwa to interact with followers. In contrast, Yoruba-based traditions like Santería and Candomblé have a more direct involvement of the Orishas, who act as intermediaries between the supreme god (Olodumare) and humans.

9. Do Voodoo ceremonies involve animal sacrifice, and how does this compare to other religions?

Yes, animal sacrifice is a component of Voodoo ceremonies, intended to feed the Lwa and ask for their blessings. This practice is also present in other African Diaspora religions such as Santería and Candomblé, where it serves a similar purpose. It should be emphasized that these sacrifices are conducted with respect and ritual cleanliness.

10. How is the societal perception of Voodoo different from other African Diaspora traditions?

Voodoo often suffers from negative stereotypes and misconceptions, partly due to sensationalist media portrayals. In contrast, other African Diaspora traditions like Santería and Candomblé, while also facing misunderstanding, tend to be more accepted within their cultural contexts. Public education about the true nature of these religions is crucial to dispel myths and promote respect.

## Conclusion

The exploration of the differences between Voodoo and other African Diaspora religions reveals a rich tapestry of cultural, spiritual, and magical traditions. Voodoo, primarily practiced in Haiti, distinguishes itself through unique rituals, deities, and ceremonies deeply rooted in West African Vodun but blended with elements of Catholicism and indigenous Taino beliefs. Unlike other diaspora religions like Santería or Candomblé, which often exhibit a more syncretic blend with Catholic saints, Voodoo maintains a distinct pantheon of Lwa, with practices like the veneration of Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte standing out in their iconography and ritual significance. Furthermore, the use of dolls and elaborate altars firmly positions Voodoo within a specific spiritual framework that, while sharing common African ancestry, diverges in its expressions and spiritual mediations.

In contrast, other African Diaspora religions such as Santería, practiced predominantly in Cuba, or Candomblé, found in Brazil, showcase different aspects in their worship and spiritual practices. Santería employs a structured hierarchy of Orishas and intricate initiation processes, while Candomblé integrates a notable emphasis on Yoruba traditions and the worship of nature deities. These religions often incorporate drumming, dance, and trance practices that, while similar in outward appearance to Voodoo’s rituals, serve distinct spiritual purposes within their unique theological frameworks. The magical practices in Voodoo, including the use of potent amulets and herbal mixtures, also mark a differentiation from the more ritualistically bound practices observed in other traditions. Thus, while sharing roots in African spirituality, Voodoo and its diaspora counterparts illustrate diverse evolutionary paths marked by cultural assimilation, spiritual adaptation, and ritualistic innovation.

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc, or its affiliates.

Continue Your Magical Journey

Free Witchcraft Starter Kit

Get 6 free printable PDFs: grimoire pages, moon calendar, spells, crystals, herbs, and tarot journal.

We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe anytime.

Enhance Your Practice

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.